Air Force:

Be sure and explore the Mission links

You are here:

Air Force/

C-119s

Career

Medals

C-119 Missions

C-130 Missions

C-141 Missions

EC-47 Missions

C-119 Missions

The Fairchild Flying Boxcar

![]()

The Fairchild C-119 started out as the C-82 Packet. Designed in 1942 with the invasion of Japan in mind, 220 were built by 1948. A C-82 is the plane seen in the 1965 Jimmy Stewart film, Flight of the Phoenix. Stunt pilot Paul Mantz built a plane supposedly from parts of the C-82, but actually parts of a C-45 and a T-6. It crashed during the filming of the movie, killing Mantz. Several people have been interested in this accident and I've added a page. You can get to it by clicking here. As you can see, the C-82 had three-bladed props and its cruising speed was 150 mph. Its cargo space was the same as a railroad boxcar, 2,870 cubic feet, so, naturally, it was never called the Packet by those who flew it, but the Flying Boxcar. That name was eventually bestowed on the C-119.

Several people have inquired about the way the Phoenix engine was started. Click on this link to learn more about the Coffman starter system. It was used on early C-82s, which was the plane in the book and first movie, but C-119s had an (A)uxiliary (P)ower (U)nit, so there is some license taken.

Flight of the Phoenix has been remade and one of the producers is the son of the original's director. It opened to very mixed reviews, from B+ to D-. Stephen Holden in the NY Times wrote as follows:

"This moth-eaten plane-crash-in-the-desert yarn, a cynical update of the far superior 1965 movie, directed by Robert Aldrich and starring James Stewart and Richard Attenborough, throws in every cheap trick in the manual to pump up your heartbeat. Watching it is the equivalent of being strapped on a treadmill and forced to trot, or of having the soles your feet tickled; you react, but involuntarily. The setting has been moved from the Sahara to the Gobi Desert and the revamped characters make up a cunningly chosen and unlikely mosaic of types that include a pretty woman, a one-eyed African-American guitarist, a Mexican-American chef, and a Saudi. Dennis Quaid is the brawny, hard-bitten pilot and Giovanni Ribisi the brainy airplane designer who, against all odds, supervises the reconstruction of the downed plane into an aeronautical phoenix."

It's not that bad and it's available on DVD. It's also worth noting that the first movie does include a woman, and a short dream sequence of a dancing Barrie Chase. The new one is a very different film and neither film is very faithful to the book, but each in its own way is worth your time, particularly if you like these airplanes. The new movie depends much more on models and CGI to depict the Pheonix although the producers used one flying C-119 and the parts of at least three others in the making of the film. No attempt was made to fly the Phoenix, which was actually made from C-119 parts. It was very nose-heavy, had no tail wheel and the insurance company wouldn't have anything to do with it, particularly in view of what happened to Paul Mantz. Some plot elements are more contrived than in the first version, including a scene in which the Phoenix is chased by horsemen and motorcycles. For those who are fans of the C-82 and the C-119, however, both films have their rewards.

![]() Ken Kopp sent me this recent picture of what may be the only C-82 still flying. It belongs to the fire-fighting outfit in Greybull, Wyoming, Hawkins and Powers. One of H-P's C-119s, Serial #10955, (below) was flown to Namibia for aerial shots for the new movie. It took 75 flying hours to get there. This plane is unusual in several ways: it has a jet engine on top, removed for the movie, and three bladed props, found only on G models designated as LS. This picture shows the plane painted for the new movie. The paint scheme was deliberately chosen to suggest water.

Ken Kopp sent me this recent picture of what may be the only C-82 still flying. It belongs to the fire-fighting outfit in Greybull, Wyoming, Hawkins and Powers. One of H-P's C-119s, Serial #10955, (below) was flown to Namibia for aerial shots for the new movie. It took 75 flying hours to get there. This plane is unusual in several ways: it has a jet engine on top, removed for the movie, and three bladed props, found only on G models designated as LS. This picture shows the plane painted for the new movie. The paint scheme was deliberately chosen to suggest water.

![]()

This company had two aircraft losses fighting fires in 2002: a C-130A in California and PB4Y Tanker 123 in Colorado, about 10 miles from our summer home. Both were determined by the FAA to be the result of main spar failures, a result of fatigue cracks in places very difficult to find without disassembling the aircraft and made even more difficult by the placement of the retardent tanks.

This company had two aircraft losses fighting fires in 2002: a C-130A in California and PB4Y Tanker 123 in Colorado, about 10 miles from our summer home. Both were determined by the FAA to be the result of main spar failures, a result of fatigue cracks in places very difficult to find without disassembling the aircraft and made even more difficult by the placement of the retardent tanks.

![]()

This is a C-119B. Note the lack of fins at the bottom of the tail section. This aircraft was with the 315 TCW, 314 TCG in Korea. Note the nose art.

This is a C-119B. Note the lack of fins at the bottom of the tail section. This aircraft was with the 315 TCW, 314 TCG in Korea. Note the nose art.

![]()

This is a C-119G, modified with two J85-GE-17 turbojets, as the YC-119K. This is the niftiest paint job I've ever seen on a C-119, but it's still not a very pretty bird. Only five were built, although more G models had jets tacked on at one time or another. Twenty-six were eventually modified and used as gunships in SEA as AC-119Ks. They had four Miniguns, a gunsight system, a flare launcher and fuselage armor, two 20-mm Vulcan Gatling-type cannons, a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) unit, forward looking and side-looking radar and a Doppler navigation system. They were known as Stingers. None returned to the U.S. There's an excellent site devoted to the AC-119s at: www.ac-119gunships.com.

This is a C-119G, modified with two J85-GE-17 turbojets, as the YC-119K. This is the niftiest paint job I've ever seen on a C-119, but it's still not a very pretty bird. Only five were built, although more G models had jets tacked on at one time or another. Twenty-six were eventually modified and used as gunships in SEA as AC-119Ks. They had four Miniguns, a gunsight system, a flare launcher and fuselage armor, two 20-mm Vulcan Gatling-type cannons, a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) unit, forward looking and side-looking radar and a Doppler navigation system. They were known as Stingers. None returned to the U.S. There's an excellent site devoted to the AC-119s at: www.ac-119gunships.com.

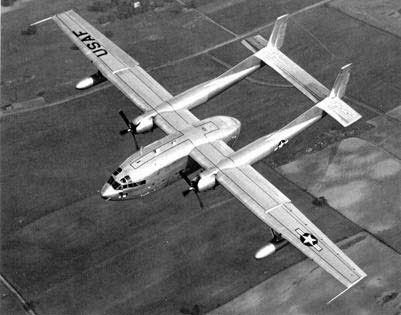

![]()

This was the last version of the C-119, the XC-119H. Only one was built. It had extended wings and carried all its fuel in two outboard external tanks, which would reduce its vulnerability to ground fire. It also meant the plane could carry a 30% greater payload with the same range and speed as the G, 2150 miles and 200 mph. Clearly the best looking of all the variants, it's still no beauty. All told, 1,183 of production model C-119s were built before production ceased in 1955.

This was the last version of the C-119, the XC-119H. Only one was built. It had extended wings and carried all its fuel in two outboard external tanks, which would reduce its vulnerability to ground fire. It also meant the plane could carry a 30% greater payload with the same range and speed as the G, 2150 miles and 200 mph. Clearly the best looking of all the variants, it's still no beauty. All told, 1,183 of production model C-119s were built before production ceased in 1955.

Seventy-nine of these were built in 1952-53 by Kaiser Motors at Willow Run, Michigan. According to Kenneth G. Keisel, who was Kaiser's chief production test pilot, all of the Kaiser-built C-119's were designated F models. The production serial numbers were 51-8101 to 51-8179 for a total of 79 produced, not 71 as is commonly reported. Of the 79, Mr. Keisel flew 69 on their maiden flights, and had air time in all but four. The C-119 at the Air Force Museum is the only known survivor of the Kaiser production. The original contract was for more aircraft, but was cut short when Kaiser's automobile production began to run into financial trouble. In addition, Fairchild required that all of Kaiser's C-119s have Fairchild ID plates mounted on them, indicating Maryland production, where all other C-119s were built, at Fairchild's Hagerstown plant. No mention of Kaiser was allowed to be placed anywhere on the aircraft, so the only way to know for sure is by the serial number, and the fact that it's an F model. This was, he says, a rather sore point for the Kaiser production crews.

My thanks to Mr. Keisel for providing this little-known piece of the C-119 story. For more information about the Kaiser airplanes from an airborne radio operator, Chuck Lunsford who has written a very good book about flying C-119s in Europe in the 1950s, click on this link. In 1955 there was a very bad accident involving two C-119s in Germany that killed 66 which Chuck has previously written about.

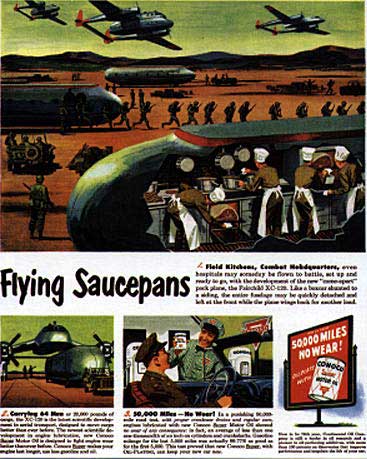

![]() There was one more attempt to improve the C-82 design. The XC-120 was a C-119 with a detachable module. Only one was built. My thanks to Jim Farrar, who flew C-119s out of Sewart AFB from '53 to '57. He found this picture in Airpower magazine. It was featured in the below Conoco ad in the middle '50s.

There was one more attempt to improve the C-82 design. The XC-120 was a C-119 with a detachable module. Only one was built. My thanks to Jim Farrar, who flew C-119s out of Sewart AFB from '53 to '57. He found this picture in Airpower magazine. It was featured in the below Conoco ad in the middle '50s.

![]()

Fairchild built a number of good airplanes: the PT-19, the C-123 (originally designed by Michael Stroukoff at Chase Aircraft), the AU 23 Peacemaker (licensed from Pilatus) and the Fairchild/Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II. Fairchild Industries still exists, but hasn't built airplanes since 1986.

This is one of the C-119Gs I flew out of Portland International for the reserves while I was in graduate school, starting in 1964. I went back on active duty in 1967 and the 119s were sent to SEA as gunships, around 1969. The squadron (349th TCW, 939th TCG, 313th TCS) then moved to McChord, at Tacoma, and flew C-141s. Today McChord is a huge reserve base, still flying 141s and now C-17s. Of course they have a museum web site.

![]()

The C-119, in all its versions, was utilitarian, slow and noisy. Like the C-82, the fuselage floor was made of wood. But it was a reliable bird and fun to fly. In those days we could do things like fly around the inside of Crater Lake and down inside the Grand Canyon. When we dropped things out the back we had to remove the clamshell doors before takeoff. Flying without them was cold, noisier and slower; removing the doors greatly increased drag. Several modifications were proposed and tried for doors that would open in flight, but none made it into production except 62 modified Gs designated as J models which had beaver-tail doors. Unfortunately those planes injured paratroops who jumped out the side doors, so the modification was dropped and the planes assigned to non-paratroop duties, such as snagging film magazines parachuted from satellites.

![]()

Airman 1st Class Curtis Chambers was a mechanic on C-119Js in 1955, training for the Corona program at a civilian airfield in Georgetown, Delaware, as a member of the 746th Troop Carrier Squadron.

"After a couple of weeks of riding in the rear of these C-119 airplanes, no doors, a cable running the length of the inside cargo section attached to a belt around my waist to prevent my falling out of the airplane, wearing a parachute, coming in 50 feet off the ground clipping the top of pine trees & scraping our recovery poles on the ground, then straight up until you were approaching stall speed. Air to air was not much better, we were always ripping off the pitot tubes with parachutes connected to drop loads. I resigned from flying. We were known as 'The Blue Nose Mules', with a blue ring painted around the nose of our planes."

The remarkable thing about this training was that it was taking place before we had any satellites in space. You can find out more about the Corona program by clicking on this link. The G also had the biggest four-bladed propellers, by Aeroproducts, ever made. The G model had huge engines: 3,500 horsepower Wright R-3350-3W Turbo Compound eighteen cylinder radial air cooled. Not as big as the B-36 engines, but very big indeed.

We spent much of our time dropping 50 gallon drums of water or army troops out the back in drop zones around Ft. Lewis, but I did take one to Goose Bay and to Ramey AFB in Puerto Rico. On that mission we lost a C-119 that was ferrying an engine to a dead bird at Grand Turk. It lost an engine as well and was never heard from again and became a part of the Bermuda Triangle myth. If you're into that sort of thing you can find out more here. Not much mystery to it; a C-119 on one engine carrying a load like that had the flight characteristics of an anvil. Also, the high frequency radios hadn't been maintained for more than 15 years so it's not surprising that no distress message was received. The radios checked out okay on the ground, to a receiver about a block away, but the one I flew didn't work the whole time we were over water.

We also flew to Alaska, once to take emergency supplies after the big earthquake in March, 1964. Fortunately the runways were unharmed. Another time we flew to Homer, on the Kenai peninsula, in support of a big training exercise. The only parking space was a tiny pad at the north end of the single runway. We were waiting to take off when a C-124 landed from the south. He misjudged the end of the runway, came in too low and clipped off his landing gear. He started sliding down the short runway toward us and there was nothing we could do but watch him come. The plane slid off to the side and came to rest in a big ditch. I had my camera handy and took the picture below from inside our aircraft. For fanatics, the tail number was 0-00114. James Madston found this page on my site and wrote that his father, Master Sergeant Noren Marvin Madston, was the flight engineer on that airplane. James was eight years old at the time, but he remembers the telephone call to his mother telling her of the crash.

![]()

The crew came out of every opening, but it didn't catch fire and nobody was injured. I can't remember exactly what they did to the pilot, Captain Brubaker, but it was nothing good.

SMSgt Ed Peltier wrote in June of 2005 with a footnote to this crash. He was with the 452nd MAW at March AFB working in production control in the middle 60s.

"We had C-124s to replace our C-119s and the flight crews were doing a lot of locals, I think -108 had a double crew, for this flight. They took off heading west and banked to the left heading south. There was a plume of dark smoke from #3 engine and we thought 'That's it,' as it had no altitude. But they came around on a short approach and landed. The base fire department was right there. As I remember they stopped about midway on the runway, and the crew came out the nose hatch/ladder. The plane was taken to the area of the big hanger. All the area in the wheel well was burned out, but there really wasn't anything going inboard that had been touched. Going outboard was another story; all along the crawl space was burned. It took awhile but the depot sent a crew and they brought the cradle and installed it all along the fuselage and wings. Our people pulled the props and engines, while the depot worked on removing all the damaged items. We were told a wing was available on a plane that had crashed in Alaska. A wing was brought in by truck, The depot made all the needed wiring harness and tubing. And of course while this was going on we used 108 for a cannibalize bird until the DCM finally had a hasp and lock installed on the hatch. This must of happened in the spring as the depot crew made a large wood table out side the hanger and played cards and drank coffee there. The wing was changed and they flew it but I was told it was a trim and balance issue that got 108 sent to the bone yard. I think we had a Capt Hill as a maintenance officer at that time. I do know that CMSGT Al Snelson was in charge of job control. I researched the tech orders for part numbers,"

Perhaps someone can prove that 108 got its wing from 00114, but the timing seems right and I'm not aware of any other C-124 crashes in AK in that period. Meanwhile, my thanks to Ed for his footnote.

So what is the cause of most aviation accidents?

"Usually it is because someone does something too much too soon,

followed very quickly by too little too late."

---Steve Wilson, NTSB investigator, Oshkosh, Wisconsin, August, 1996.

This page gets more attention than any other of my aircraft pages (it has been accessed more than 75,000 times since I first posted it in 1996 and more than 20,000 times just since 2005), and I welcome any mail. I frequently alter it to reflect the mail and/or pictures people send me.

Walter E. Wallis, of the 23rd Infantry Regiment wrote me several years ago and said

"In April or May of 1951, near the Imjin Valley in Korea, I was in the chow line listening to 5 batteries of artillery firing up a fog-shrouded valley. Suddenly, a formation of C-119s emerged from the fog toward us. The artillery, some vt [proximity] fused, exploded among the planes. I believe five went down, including one that did most of a loop. We never did find out how many were killed or why the planes were where they were. Since we had just emerged from Chipyongni a month ago, where C-119s delivering supplies were the only thing that kept us in the war, I felt especially bad."

And speaking of Korea, there's an interesting story on this page about Gerry Storm's assignment in Korea in the 1950s. Here is another link to a very good C-119 site. I had 484 hours in C-119s.

"The C-119, in all its versions, was utilitarian, slow and noisy...But it was a reliable bird and fun to fly."

Career

Medals

C-119 Missions

C-130 Missions

C-141 Missions

EC-47 Missions